Why people do what they do is always and everywhere a most interesting question, and a pressing one. I do not know if there are any really completely satisfying answers to it, but the most satisfying of the available answers I have yet heard is this one. S. John Chrysostom’s paschal homily is an obvious choice for a Christian to make, and particularly a Christian of Eastern persuasion. (I can claim no bonus points for originality.) But from the first time I heard the sermon preached, it has continued to satisfy the whole of me—emotions as well as intellect—more than any other short statement of belief (or unbelief) I can call to mind. It surprises anew, and satisfies anew, every year.

After the long silence of Lent, this one text—please forgive my presumption!—seems to make everything else in the Church, worthwhile; as this one day—the day of Resurrection—makes all life worthwhile.

Christ is risen! Happy feast!

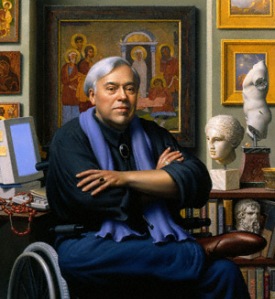

vozradujemsja

Victor de Villa Lapidis

THE CATECHETICAL SERMON OF SAINT JOHN CHRYSOSTOM, ARCHBISHOP OF CONSTANTINOPLE

If any man be devout and love God,

Let him enjoy this fair and radiant triumphal feast!

If any man be a wise servant,

Let him rejoicing enter into the joy of his Lord.

If any have labored long in fasting,

Let him now receive his recompense.

If any have wrought from the first hour,

Let him today receive his just reward.

If any have come at the third hour,

Let him with thankfulness keep the feast.

If any have arrived at the sixth hour,

Let him have no misgivings;

Because he shall in nowise be deprived therefore.

If any have delayed until the ninth hour,

Let him draw near, fearing nothing.

If any have tarried even until the eleventh hour,

Let him, also, be not alarmed at his tardiness;

For the Lord, who is jealous of his honor,

Will accept the last even as the first;

He gives rest unto him who comes at the eleventh hour,

Even as unto him who has wrought from the first hour.

And he shows mercy upon the last,

And cares for the first;

And to the one he gives,

And upon the other he bestows gifts.

And he both accepts the deeds,

And welcomes the intention,

And honors the acts and praises the offering.

Wherefore, enter you all into the joy of your Lord;

And receive your reward,

Both the first, and likewise the second.

You rich and poor together, hold high festival.

You sober and you heedless, honor the day.

Rejoice today, both you who have fasted

And you who have disregarded the fast.

The table is full-laden; feast ye all sumptuously.

The calf is fatted; let no one go hungry away.

Enjoy ye all the feast of faith:

Receive ye all the riches of loving-kindness.

Let no one bewail his poverty,

For the universal kingdom has been revealed.

Let no one weep for his iniquities,

For pardon has shown forth from the grave.

Let no one fear death,

For the Savior’s death has set us free.

He that was held prisoner of it has annihilated it.

By descending into Hell, He made Hell captive.

He embittered it when it tasted of His flesh.

And Isaias, foretelling this, did cry:

Hell, said he, was embittered,

When it encountered Thee in the lower regions.

It was embittered, for it was abolished.

It was embittered, for it was mocked.

It was embittered, for it was slain.

It was embittered, for it was overthrown.

It was embittered, for it was fettered in chains.

It took a body, and met God face to face.

It took earth, and encountered Heaven.

It took that which was seen, and fell upon the unseen.

O Death, where is thy sting?

O Hell, where is thy victory?

Christ is risen, and thou art overthrown!

Christ is risen, and the demons are fallen!

Christ is risen, and the angels rejoice!

Christ is risen, and life reigns!

Christ is risen, and not one dead remains in the grave!

For Christ, being risen from the dead,

Is become the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep.

To Him be glory and dominion

Unto ages of ages.

Amen.